The rise of cheap but capable ARM processors, and the saturation of internet connectivity with Wi-Fi and cellular, has led to the rapid spread of Internet of Things devices. IoT can now be found across the consumer and enterprise landscape, finding itself particularly well suited for industrial, campus, and municipal applications. But has security risen to meet the sudden influx of IoT devices? Not quite. Rich Stroffolino breaks down the problem, why enterprises will eventually catch up, and what the regulatory landscape might look like when they do.

Transcript of Checksum Episode 2: Is IoT Security a Nightmare?

First it was a dream, then it was a reality, now its a nightmare. No, I’m not talking about the DC cinematic universe. I’m talking about the internet of things.

Up until the last decade, IoT seemed like a fun idea whose time would never come. Sure you’d have your occasional Chumby sitting on a nightstand, but the idea of a pervasive ecosystem of internet-connected non-computer things that was both affordable AND useful seemed like it was years away. But the pervasive nature of cheap ARM chips and ubiquitous WiFi suddenly made IoT not just possible, but seemingly easy.

Suddenly we were awash in internet-connected devices. Sure the Amazon Echo family was an early success story, and while it jumped out to an early market share lead, the bigger story of IoT is the vast array of white box options from overnight OEMs. Having Google or Amazon running an IoT ecosystem comes with a raft of completely justifiable privacy concerns, but having thousands of devices from unknown manufacturers is a genuine security crisis.

There’s, of course, the creepy risk to individuals. A quick search on Shodan will demonstrate just how perilous the IoT landscape is, with just an IP address and a stock login, you can often get access to printers, video cameras, and more.

Add to it the fact that these devices are also the perfect vector for botnets to launch DDoS attacks. Figuring out how to own one type of device with low security means you can suddenly have your botnet installed on thousands of devices. The thing that makes IoT interesting to consumers, it’s low maintenance, appliance-like operation, and also has the same benefits for malicious acts.

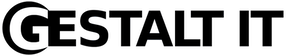

Enterprise use cases aren’t exempt from this either. A recent report by security researchers at IOActive found security exploits within Long Range Wide Area Networks, or LorRaWAN, that use radios for low powered connectivity for IoT sensors back to home base. Don’t get me wrong, this is a really useful connection standard for battery-powered devices in the field that need to sip power but remain connected, think of things like weather monitoring or traffic management sensors. But the researchers found that in many instances, organizations deploying them left their encryption keys in plane view, from leaving on a QR code on the device that contained device IDs, security keys, and more, to keeping in hard-coded encryption keys from open source libraries, meaning you were a search on GitHub away from breaking encryption!

While enterprise exploits are worrying, I think this is just a reflection of IT culture not realizing the implications of having end points in an IoT form factor. The same standards that might secure a server in a data center or even on edge site don’t work on an IoT device that’s mostly unattended and potentially public-facing its entire life. Enterprises have a vested interest in changing their IT culture to adjust to that expectation, and I suspect these growing pains will lessen over time. Not that that excuses companies from liability.

But we’re starting to see regulatory scrutiny hit the consumer IoT side. The UK’s Department for Culture, Media and Sport and National Cyber Security Center recently proposed measures to deal with the issues. They would require all internet-connected device passwords to be unique and not offer a stock password factory reset option, basically so someone doesn’t reset it a known stock answer. IoT manufacturers would also have to provide a public point of contact so any can report a vulnerability and provide a timely response. And devices must have an explicitly stated minimum length of support time for things like security updates from point of sale.

These mirror similar regulatory rumblings coming from the EU and the US. These requirements will raise the minimum threshold needed to sell IoT devices to a consumer. This will almost certainly restrict who can market an IoT device. Gone are the days of someone rebranding something they bought on Alibaba and dumping it on the market. Requiring a place to report bugs and having to respond in a timely fashion is a good first step, but not enough. Let’s face it, Amazon, Google, and Apple already have responsible systems in place to report bugs, and enough of a public profile to pressure them to fix them quickly. But for smaller IoT manufactures, the problem is how to get eyes of security researchers on them. Requiring some sort of bug bounty program, while probably not legislatively possible, would go much farther to get eyes on these smaller devices, and help resolve the most table stakes issues. Because we already know that there’s enough of an incentive for black hats to look to exploit these devices.

That’s it for me. For links to the stories and reports referenced in this video, check out the description below, and remember to check out Gestalt IT.com for more enterprise IT breakdowns.