I’ve recently been evaluating some of the new features in VMware vSphere to see what use they would be to my current employer. One of the areas that I touched upon in my “what’s new in vSphere Storage” blog post was thin provisioning. I wanted to come back and cover this particular topic in more detail as it’s a key feature and it’s available throughout all versions of vSphere so I’m sure everyone will be interested in it.

What is Thin Provisioning?

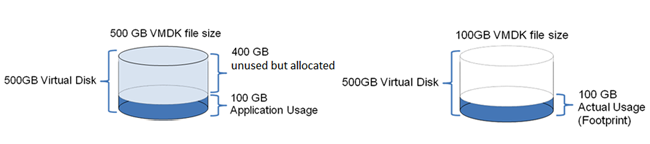

Thin Provisioning in it’s simplest form is only using the disk space you need. Traditionally with virtual machines if you create a 500GB virtual disk it will use 500GB of your VMFS datastore. With Thin Provisioning you can create a 500GB virtual disk, but if only 100GB is in use only 100GB of your VMFS datastore will be utilised. Credit to Chad Sakac for the diagrams below.

How does it work in vSphere?

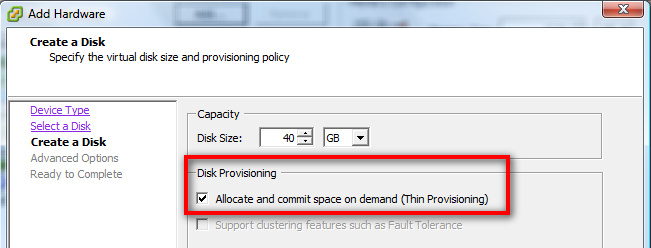

Thin Provisioning is being heralded as something new with vSphere, when in truth it was already available in VI3. In VI3 creating a thin provisioned disk involved using vmkfstools and was also not a production supported VM configuration. Now in vSphere the creation of thin provisioned disks can be carried out from the VI Client (see below) and is a supported production configuration for a VM.

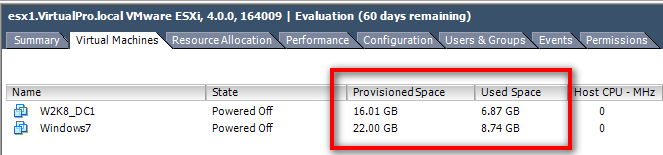

It’s as simple as checking a check box, the results are pretty good to. Below you can see I have created two thin provisioned VM’s on my new ESX4i host and you can see the provisioned space and the used space stats being shown in the VI Client.

What are the benefits?

The thin provisioning feature is perfect for my home lab environment where disk space is at a premium, but how does it translate into real world implementations of ESX. Well I for one have been looking at exactly this to identify what benefits could be achieved within my employers ESX estate. A quick audit found that our development and system test ESX environment was running at 48% disk utilisation, so straight away thin provisioning would save us 52% on storage capacity used. Paul Manning of VMware mentioned on a recent communities podcast that on average vSphere would save users 50% on storage. This is possibly not such a big thing when your talking about test environments, but when you move up to production SAN Storage, saving 50% on an expensive SAN array is a very real and tangabile cost saving. One that people should definately take into account when making a cost benefit case for buying or upgrading to vSphere.

What are the potential downsides?

One of my personal concerns with thin provisioning is the potential overhead on any write activity that would requires the extension of the VMDK file. To me there is an obvious VMFS operation that needs to take place there which would add to the overall time to complete the disk write. When there is a requirement to expand a disk, the VMDK files will increase in increments based on the block size of the underlying VMFS partition, 1MB, 2MB, 4MB or 8MB. So the overhead may be smaller if your VMFS has been formatted with a bigger block size, i.e. for a 16MB write it only has to expand 2 blocks when the VMFS block size is 8MB but would have to expand 16 blocks if it was formatted with the 1MB block size. I can imagine this percieved overhead could put people off using thin provisioned disks for certain production based environments, especially those where there is a lot of write I/O activity, SQL Server or Exchange for example. To counteract that though, the improvements in the VMware I/O Stack should compensate for this performance overhead. This could potentially leave you in a situation where you’ve reduced a VM’s storage footprint and still have performance equal to that experienced in VI3, possibly not a bad trade off. I’d also expect people running their VMware environment on enterprise SAN technologies from the likes of EMC or NetApp to notice minimal performance impact with thin provisioning as SAN memory caches help take up the strain.

Another downside is if you want to use VMware Fault Tolerance to protect a VM then you cannot use thin provisioned disks. To be honest this is a small issue as Fault Tolerance protection is most likely going to be on virtual machines that are important to your organisation. These machines are probably the ones you wouldn’t thin provision in the first place for performance reasons.

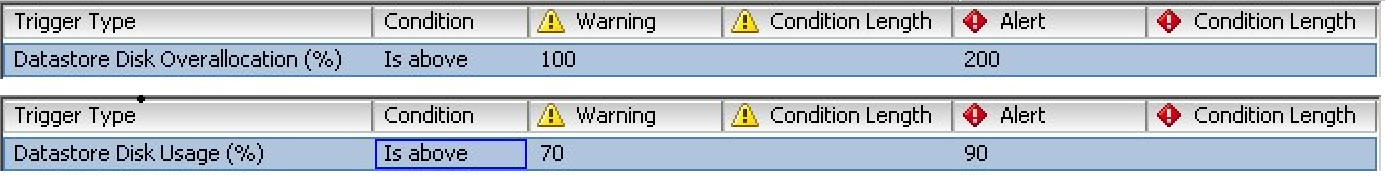

Thin provisioning creates it’s own unique problem in that what we’re basically doing here is over provisioning the storage. You need to keep a very close eye on thin provisioning as it’s quite feasabile that your VMFS datastore could fill up and your virtual machines fall over. Not what you want to come into on a Monday morning, or any morning for that matter. So you need to monitor your storage and ensure that there is enough free space. One of the simplest ways to do this is through the use of the new alarms in vSphere that allow you to alert on datastore usage and datastore over provisioning. These should keep you from filling a datastore and killing your VM’s or ESX Servers

One gotcha that you should watch out for is VM swap files, as these are usually stored with your virtual machines vmdk files in the VMFS datastore. In VI3 the swap file was not deleted when a VM was powered down, in vSphere the swap file is deleted on power down and recreated when the VM is powered up. You should be aware of this when over provisioning storage as you could get into a situation whereby you find you can’t power on a VM because there isn’t enough space for the swap file to be created. This becomes more likely as servers and VM configuration maximum’s increase, if you have a VM with 20GB of RAM it’s going to need 20GB of disk space for the swap file. if you have 256GB of RAM in your vSphere host and you allocate it all out to VM’s then you need to think about the 256GB of disk capacity required to service virtual machine swap files.

Storage vMotion

If you’ve already got a VI3 environment then the chances are that your VM’s aren’t thin provisioned, how on earth are you going to take advantage of this new feature? Well if you have purchased a vSphere edition that supports storage vMotion then you can of course migrate the underlying storage and have it thin provisioned during the move. This should allow existing VI3 customers to claim back a lot of space, as I mentioned before I found that our development and test VI environments were only 48% utilised. If I storage vmotion all those VM’s and thin provision at the same time I will free up about 1.5TB of storage that wasn’t being used in the first place.

I’ve included a video below which demonstrates the Storage vMotion and thin provisoning features in vSphere quite nicely, enjoy!

Even without storage vMotion you can change a machine to thin provisioning, it takes you downing the machine then migrating it to another datastore, it will give you the option to enable thin provisioning at that time.

Check out this great article & demo of ThinProvisioning on #vSphere

can someone comment on why you would do VSphere thin provisioning vs native array based thin provisioning?

Curious,

(is this a Dear Abbey column?)

What if your storage device doesn't do thin provisioning? (Storage

servers via NFS) What about for VMs on local ESX storage?

good point, in other words, vsphere thin provining is like a poor man's thin provisioning? if you have arrays with thin provisioning capability, would you still use vsphere thin provisioning or array based thin provisioning?

There is another side to it, what skill sets do you have in house, what is your appetite for risk and what are your people more comfortable managing. I can hand on heart say at my work people are more comfortable with VMware than they are with our EMC kit. They'd be more capable of reacting to an issue within vCenter than they would within Navisphere. That's not to say our approach is the right approach though, I myself need to spend more time looking into EMC array based Thin provisioning because at the moment I'm more comfortable with the VMware side, simply because I'm new to EMC.

However, that's not to say you can't combine the two, thin on thin so to speak. Chad Sakac at EMC wrote a good article on this way back when vSphere thin provisioning came out. The simple examples given I think show the extra complexity you introduce with thin on thin.

http://virtualgeek.typepad.com/virtual_geek/200…

There is another side to it, what skill sets do you have in house, what is your appetite for risk and what are your people more comfortable managing. I can hand on heart say at my work people are more comfortable with VMware than they are with our EMC kit. They'd be more capable of reacting to an issue within vCenter than they would within Navisphere. That's not to say our approach is the right approach though, I myself need to spend more time looking into EMC array based Thin provisioning because at the moment I'm more comfortable with the VMware side, simply because I'm new to EMC.

However, that's not to say you can't combine the two, thin on thin so to speak. Chad Sakac at EMC wrote a good article on this way back when vSphere thin provisioning came out. The simple examples given I think show the extra complexity you introduce with thin on thin.

http://virtualgeek.typepad.com/virtual_geek/200…

Great article, short and to the point, very informative, thanks!

Don't trust “Browse Datastore” of the ESX console

Using ssh ,check the datastore, /vmfs/volumes

You will find the xxx-flat.vmdk (hidden on ESX console), note the size of this file

No “thin”

Don't trust “Browse Datastore” of the ESX console

Using ssh ,check the datastore, /vmfs/volumes

You will find the xxx-flat.vmdk (hidden on ESX console), note the size of this file

No “thin”