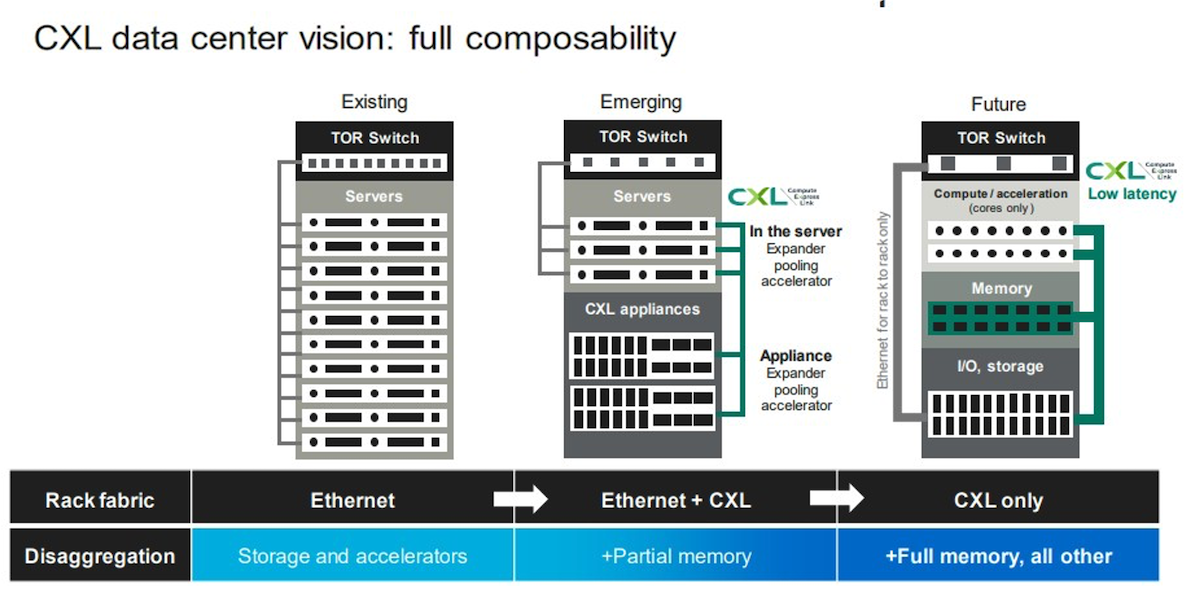

Compute Express Link (or “CXL”), discussed in the Gestalt IT white paper titled “Digital Infrastructure at Datacenter Scale“, is a next generation technology intended to connect computer resources in the datacenter together at tremendous speed. I say “in the datacenter” and not “in a server” intentionally, as the finalized model of CXL will have the resources that used to make up a server sitting in pools that can be utilized by any server that needs them. This is essentially the idealized form of what has been called ‘composable infrastructure’ for many years now.

Improving on Composable Infrastructure

Initial attempts at composable infrastructure had datacenter designs centered around blade chassis. These chassis had any number of slots that could be filled with different types of processing power, and in some cases even different types of processors (i.e., x86 blades side by side with IBM Power systems, for example.) Some blades would be able to host a number of hard disks, to provide in-chassis backplane connectivity that would be fast, simple, and secure. CXL will take this idea the next step further.

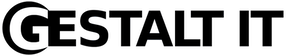

The CXL technology is spearheaded by Intel, and work began on it in 2019. The CXL specification works over the PCIe bus and allows ‘accelerators’ to be connected to it. The initial versions of the specification allow this connection locally for whatever type of resource accelerator you need – memory, graphics cards, storage, etc.- being connected via PCIe. There are several technologies that already exist (or will be released in the near future) that will take advantage of this speed and access to the processor. For example, SK Hynix is releasing DDR5 DRAM-based CXL memory modules at the beginning of next year. (Samsung announced a similar product in 2021 that is also ready to go.)

Memory and CXL

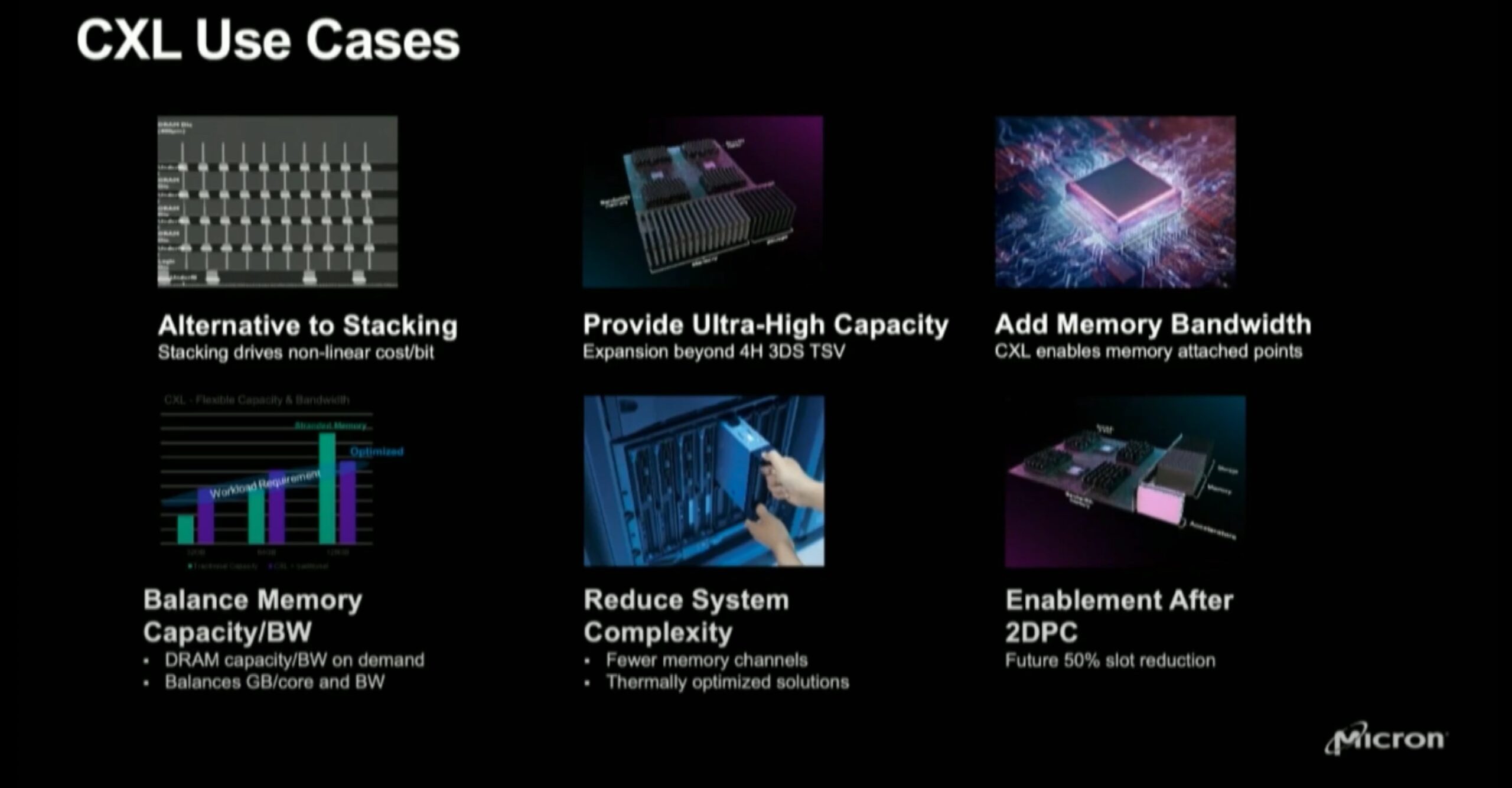

Using the PCIe bus will allow a significant expansion of available memory bandwidth. Future iterations of persistent memory modules are also in the works to supplant the Intel Optane line of memory products. Other companies are also in the mix- the CXL Consortium has a vast collection of companies already onboard, from Intel to HPE, Google Cloud and Samsung, all sharing statements of support for the future of the specification.

Using PCIe to expand available memory and bandwidth on-system by at least 50% will be exciting. However, future implementations of CXL will take this idea even further and allow an entire private CXL network that will allow connection across a datacenter.

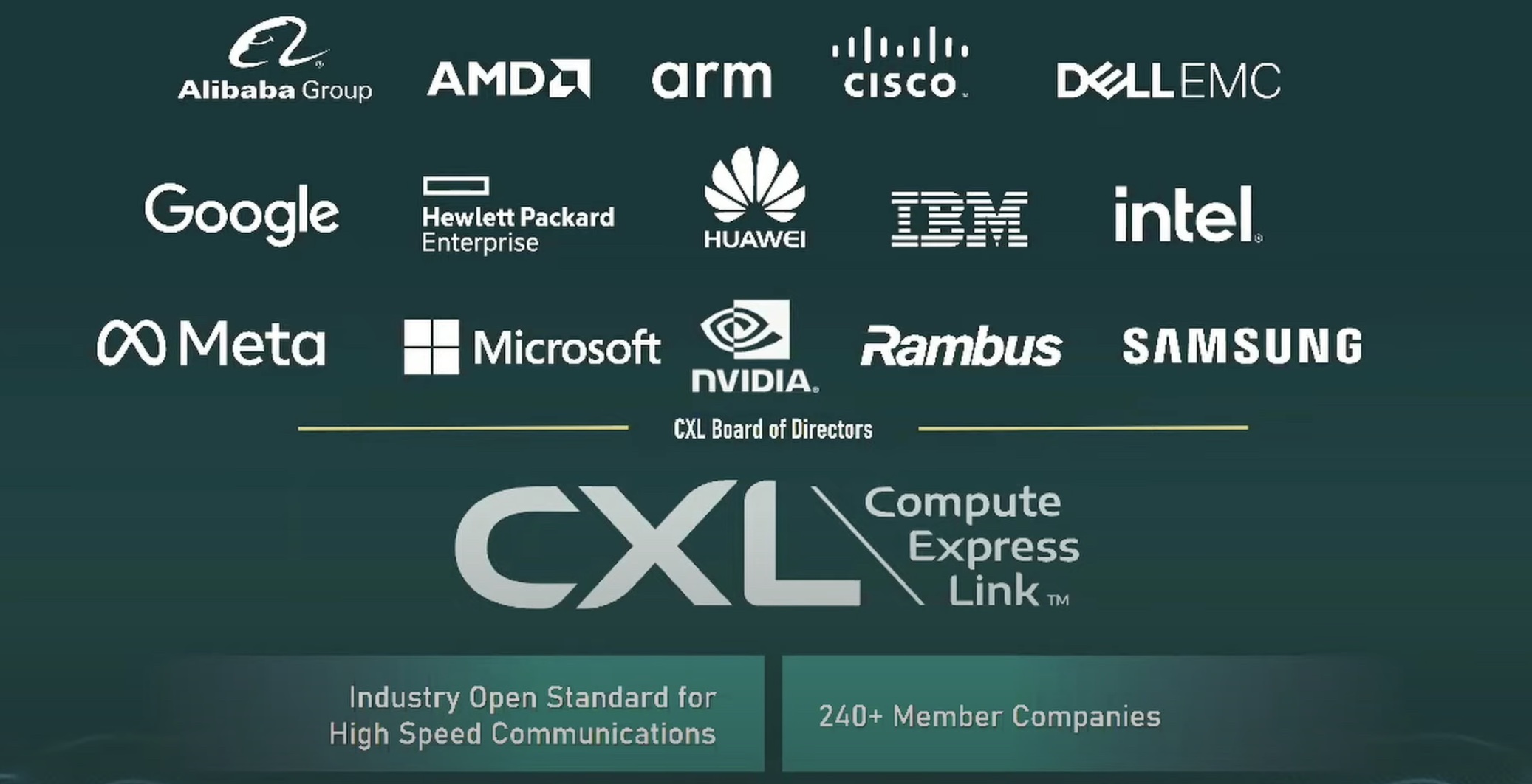

What you will have are connected components packed with memory, for example, that can be used by any system in the rack. Deployments and allotments of resources will be based on policies controlled by a CXL management server, and component communications done over secure, private CXL networks at PCIe speeds. If you need more memory, you expand it based on the available pool of resources. CXL 3.0, the next major version on the roadmap, will do this same thing for all the other system resources that previously had to be installed directly in system. This, in effect, is the hardware version of a VMware deployment- enabling previously impossible features such as assigning memory to running bare-metal systems without requiring a reboot.

The CXL specification has one more key feature: Backwards compatibility. The upcoming release of the Intel Sapphire Rapids line of CPUs will enable people to take advantage of CXL 2.0 products, such as the memory products we have mentioned. It will also mean that systems purchased for 2.0 will be able to utilize the 3.0 products that are on the CXL roadmap just as easily. Consider the implications of being able to recompose a system on the fly, assigning memory or GPUs or NICs where they are needed- and re-assigning them elsewhere if that need dissipates. CXL will make good on the promise of truly composable infrastructure.